“It’s tempting to ask why if you fed your neighbors during the time of the earthquake and fire, you didn’t do so before or after.”

― Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell

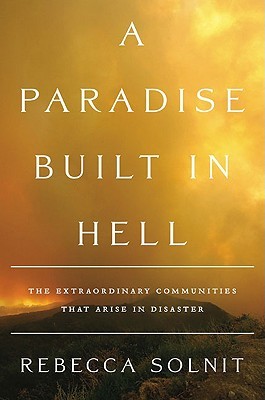

“A Paradise Built in Hell” is the first book I have read that could be categorized as “disaster sociology.” It is, however, far from a dry academic textbook. Rebecca Solnit references many natural and man made disasters including; the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, the 1917 explosion in Halifax, the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, all in order to make the case that, counter to the popular narrative, when face with a crisis most people’s default response is that of altruism and kindness, not a descent into madness.

Solnit’s various case studies reveal that we are far more likely to help our neighbor during a disaster than we are to harm our neighbor. According to Solnit, the people most prone to panic are the “elites” in power who fear losing their control and influence when the normal social order is disrupted. It is the fear of anarchy, not anarchy itself, which causes the most damage to communities in the aftermath of a disaster.

A major focal point of this book is the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the negative effect that the fear of our neighbors had on relief efforts. In the case of Hurricane Katrina, unsubstantiated rumors of looting, race wars, and gang rapes flooded the media and affected the ways in which the government responded to the disaster. It was not until long after the fact that we learned that these claims were highly exaggerated and largely baseless.

The testimonies from those who were in New Orleans during and after the hurricane paint a much more benevolent picture of how people reacted to the crisis at hand. The vast majority testified, not of a return to animistic savagery, but of common acts of kindness and a communal sense of unity. Why then are we so prone to assume the worst of our neighbors in a crisis? Why do we think that, when society crumbles, we will become our own worst enemy? While the author does not offer a one-size-fits all answer to these questions, I think she comes upon something profound when she argues that disasters disrupt our lives and force us to live in a new reality, if only until we find a new normalcy. When we find ourselves in the midst of a disaster, we are forced into a new way of thinking. We are forced to become hyper-aware of our present moment and the needs around us. I would argue that these moments tend to reveal the best in humanity, because they force us to wrestle with who we truly are.

As a Christian my understanding of human nature is shaped by the often misunderstood doctrine of “total depravity.” This is not the belief that people are incapable of good, that humanity is wicked to the core, or that people are somehow unable to know good from evil. Rather, total depravity is the belief that human nature is marred by sin to some degree at every level and that we cannot achieve a standard of goodness that would merit God’s gift of salvation. Human beings are said to have been made in the image of God, and while none of us are without guilt, we are also never beyond the mercy and grace of God. But if we are totally depraved, how can we account for the goodness we see in humanity? How can we account for the selfless acts of charity seen whenever a crisis arises?

A Christian term for understanding the goodness of humanity which Rebecca Solnit argues for in her book is “common grace.” Not to be confused with saving grace, common grace is a term for the grace and goodness that God has made known to all humanity. This grace is a goodness which benefits the whole human race, and is certainly not limited to those who profess faith in Christ. It is common grace that allows human beings, regardless of faith, to have some consciousness of the difference between right and wrong and the awareness that human beings have a value that transcends our calculation. Each of us is endowed with the dignity of existing as a responsible being. We have a great capacity for love and goodness, even if we are not able to make sense of these concepts apart from the God who made us. Whether we realize it or not, we are prone to do good, not only out of a sense of self-respect and of respect for others but of respect for God.

Our problem is not that we are incapable of good, but that we are often so bound up in sin, self-centeredness, and our various cultural idolatries, that our imago dei (our image of God) has little opportunity to shine forth. Perhaps disasters, like the ones featured in this book, provide a rare and temporary opportunity to live as human beings stripped of these layers of depravity. Maybe disasters and moments of crisis, are opportunities to see that we are more than base creatures motivated by selfish impulses.

It is a testimony to the pervasiveness of our sin nature that these moments rarely outlive the crisis. Once homes are rebuilt and the old systems start running again, people will inevitably return to the rat race of modern living. The sense of communal unity always fades and we often return to the old tribalistic ways of thinking. Neighbors who ban together in a crisis may cease to speak to one another when the crisis has faded. And yet, maybe there is something of value to be found in these moments of great disruption. When the world we live in feels as if it has been turned upside down, we might be able to catch a glimpse a of a better world than the one we lost, even if only for a moment. Perhaps it is in the darkest moments that we see, not just who we are, but who we were meant to be?